In

1868 Black Kettle was an ageing Cheyenne chief who wanted nothing more than to

live in peace with the white man. Four years earlier his village along the Sand

Creek had been torn to pieces by a vicious attack under the command of Colonel

John Chivington. Now, though Black Kettle had encamped on the banks of the

Washita River, some 40 miles east of Oklahoma’s Antelope Hills. Although he

was guaranteed protection under the Medicine Lodge Treaty, Black Kettle didn’t

want to take any chances on a repeat of Sand Creek. He approached General

William B. Hazen at Fort Cobb, 100 miles away, and asked for permission for his

people to move closer to the fort to afford them more protection. Hazen assured

Black Kettle that this would be fine and that the village need not fear an

attack from the United States army.

In

1868 Black Kettle was an ageing Cheyenne chief who wanted nothing more than to

live in peace with the white man. Four years earlier his village along the Sand

Creek had been torn to pieces by a vicious attack under the command of Colonel

John Chivington. Now, though Black Kettle had encamped on the banks of the

Washita River, some 40 miles east of Oklahoma’s Antelope Hills. Although he

was guaranteed protection under the Medicine Lodge Treaty, Black Kettle didn’t

want to take any chances on a repeat of Sand Creek. He approached General

William B. Hazen at Fort Cobb, 100 miles away, and asked for permission for his

people to move closer to the fort to afford them more protection. Hazen assured

Black Kettle that this would be fine and that the village need not fear an

attack from the United States army.

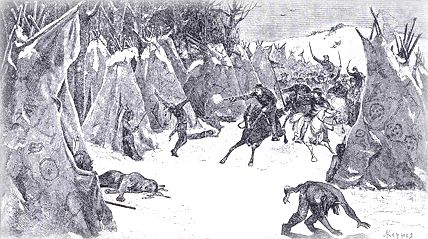

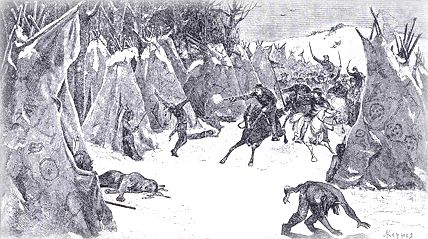

Despite such assurances, however, November of 1868 did, indeed, see a command

of soldiers advancing on Black Kettle’s village. A part of General Philip

Sheridan’s winter campaign, the outfit in question was the Seventh Cavalry,

under the control of the dashing young Civil War hero, George Armstrong Custer.

After a gruelling three day march over snow covered frozen country, Custer

slowed his advance. He sent his second in command, Major Joel H Elliot, ahead on

a scouting mission. Elliot soon found tracks leading to a large Indian village.

He reported back to Custer that he had found signs of a village ahead. Custer

immediately concluded that they were hostiles and made preparations for the

attack.

Meanwhile Black Kettle had just returned home from his conference with

General Hazen. He called a council to relay Hazen’s assurances to the people

that there would be no attack by the soldiers. The day after that council Black

Kettle was awoken with the words “Soldiers! Soldiers!” The old man grabbed

his rifle and fired a warning shot.

Black Kettle advanced to the head of the village to meet the soldiers. He

hoped to talk peace and avoid any bloodshed. But this was not to be. The

soldiers poured into the village from all four sides. Black Kettle still

attempted to bring some sanity, hoisting a white flag besides the Starts and

Stripes that already fluttered above his tipi. Within minutes, though, both

Black Kettle and his wife had been cut down in a hail of bullets. Black

Kettle’s fourteen year old son was killed soon thereafter in hand to hand

combat. Warriors rushed from their tipis and made for the ravine where they

could set about mounting a defence. Yet Custer had secured the village within

ten minutes.

Black Kettle advanced to the head of the village to meet the soldiers. He

hoped to talk peace and avoid any bloodshed. But this was not to be. The

soldiers poured into the village from all four sides. Black Kettle still

attempted to bring some sanity, hoisting a white flag besides the Starts and

Stripes that already fluttered above his tipi. Within minutes, though, both

Black Kettle and his wife had been cut down in a hail of bullets. Black

Kettle’s fourteen year old son was killed soon thereafter in hand to hand

combat. Warriors rushed from their tipis and made for the ravine where they

could set about mounting a defence. Yet Custer had secured the village within

ten minutes.

Indians

in neighbouring villages now rushed to the scene of the carnage to take on the

soldiers who had attacked their brothers. Soon Custer’s men were outnumbered.

Just as it seemed that the tables were about to be turned on Custer, his supply

wagons and a mounted escort arrived on the scene. This sufficiently distracted

the Indians and Custer’s regiment was able to pull out. He soon realised that

Major Elliot and his men were missing, however. Custer made the decision not to

look for them, one for which he would be resented for the rest of his life.

Before pulling out of the village, the lodges were burnt. The Indians lost 4000

arrows, 500 pounds of lead and an equal amount of powder. 875 horses were shot

to death. However, Custer released his 53 women and child prisoners before

leaving.

Rather than high tailing it like a scared puppy, Custer reformed his men and

boldly marched them right up the middle of the Washita as the band boomed out ,

“Ain’t I Glad to Get Out of the Wilderness.” This took the Indians by

surprise and they gradually withdrew as Custer’s men advanced. They halted at

the next camp they came to, acting as if they were about to attack this one as

well. He knew, however, that the Indians would have set a trap for him and

eluded them. From there Custer’s regiment managed to make their escape.

Custer’s losses amounted to Major Elliot, a Captain Louis M. Hamilton and

19 enlisted men. Three officers and 11 men were wounded. The official count of

Indian dead was 103.

The Battle of the Washita was an inconsequential engagement in the scheme of

things. It did, however, gain publicity and prominence for the man who led the

attack. The Indians, however, smarted badly from this unprovoked attack on a

friendly encampment. Eight years later they would exact their revenge along the

banks of another river – the Little Big Horn.

In

1868 Black Kettle was an ageing Cheyenne chief who wanted nothing more than to

live in peace with the white man. Four years earlier his village along the Sand

Creek had been torn to pieces by a vicious attack under the command of Colonel

John Chivington. Now, though Black Kettle had encamped on the banks of the

Washita River, some 40 miles east of Oklahoma’s Antelope Hills. Although he

was guaranteed protection under the Medicine Lodge Treaty, Black Kettle didn’t

want to take any chances on a repeat of Sand Creek. He approached General

William B. Hazen at Fort Cobb, 100 miles away, and asked for permission for his

people to move closer to the fort to afford them more protection. Hazen assured

Black Kettle that this would be fine and that the village need not fear an

attack from the United States army.

In

1868 Black Kettle was an ageing Cheyenne chief who wanted nothing more than to

live in peace with the white man. Four years earlier his village along the Sand

Creek had been torn to pieces by a vicious attack under the command of Colonel

John Chivington. Now, though Black Kettle had encamped on the banks of the

Washita River, some 40 miles east of Oklahoma’s Antelope Hills. Although he

was guaranteed protection under the Medicine Lodge Treaty, Black Kettle didn’t

want to take any chances on a repeat of Sand Creek. He approached General

William B. Hazen at Fort Cobb, 100 miles away, and asked for permission for his

people to move closer to the fort to afford them more protection. Hazen assured

Black Kettle that this would be fine and that the village need not fear an

attack from the United States army.

Black Kettle advanced to the head of the village to meet the soldiers. He

hoped to talk peace and avoid any bloodshed. But this was not to be. The

soldiers poured into the village from all four sides. Black Kettle still

attempted to bring some sanity, hoisting a white flag besides the Starts and

Stripes that already fluttered above his tipi. Within minutes, though, both

Black Kettle and his wife had been cut down in a hail of bullets. Black

Kettle’s fourteen year old son was killed soon thereafter in hand to hand

combat. Warriors rushed from their tipis and made for the ravine where they

could set about mounting a defence. Yet Custer had secured the village within

ten minutes.

Black Kettle advanced to the head of the village to meet the soldiers. He

hoped to talk peace and avoid any bloodshed. But this was not to be. The

soldiers poured into the village from all four sides. Black Kettle still

attempted to bring some sanity, hoisting a white flag besides the Starts and

Stripes that already fluttered above his tipi. Within minutes, though, both

Black Kettle and his wife had been cut down in a hail of bullets. Black

Kettle’s fourteen year old son was killed soon thereafter in hand to hand

combat. Warriors rushed from their tipis and made for the ravine where they

could set about mounting a defence. Yet Custer had secured the village within

ten minutes.